Back التبت تحت حكم سلالة تشينغ Arabic Tibet sous la tutelle des Qing French Tibet di bawah kekuasaan Qing ID 청나라 치하 티베트 Korean Tibet di bawah pemerintahan Qing Malay Tibete sob o domínio Qing Portuguese Tibet dina Kakawasaan Qing Sundanese குயிங் ஆட்சியில் திபெத் Tamil Тибет у Новий час (1642-1912) Ukrainian Tây Tạng thuộc Thanh Vietnamese

| Tibet under Qing rule | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protectorate and territory of the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||

| 1720–1912 | |||||||||||

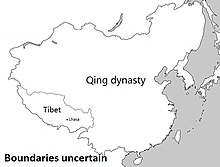

Tibet within the Qing dynasty in 1820. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Lhasa | ||||||||||

| • Type | Buddhist Theocracy headed by Dalai Lama or regents under Qing protectorate[1][2] | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 1720 | |||||||||||

• Tibetan border established at Dri River | 1725–1726 | ||||||||||

| 1750 | |||||||||||

| 1788–1792 | |||||||||||

| 1903–1904 | |||||||||||

| 1910–1911 | |||||||||||

| 1912 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| History of Tibet |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

|

Tibet under Qing rule[3][4] refers to the Qing dynasty's rule over Tibet from 1720 to 1912. The Qing rulers incorporated Tibet into the empire along with other Inner Asia territories,[5] although the actual extent of the Qing dynasty's control over Tibet during this period has been the subject of political debate.[6][7][8] The Qing called Tibet a fanbu, fanbang or fanshu, which has usually been translated as "vassal", "vassal state",[9] or "borderlands", along with areas like Xinjiang and Mongolia.[10] Like the preceding Yuan dynasty, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty exerted military and administrative control over Tibet, while granting it a degree of political autonomy.[11]

By 1642, Güshi Khan of the Khoshut Khanate had reunified Tibet under the spiritual and temporal authority of the 5th Dalai Lama of the Gelug school, who established a civil administration known as Ganden Phodrang. In 1653, the Dalai Lama travelled on a state visit to the Qing court, and was received in Beijing and "recognized as the spiritual authority of the Qing Empire".[12] The Dzungar Khanate invaded Tibet in 1717 and was subsequently expelled by the Qing in 1720. The Qing emperors then appointed imperial residents known as ambans to Tibet, most of them ethnic Manchus, that reported to the Lifan Yuan, a Qing government body that oversaw the empire's frontier.[13][14] During the Qing era, Lhasa was politically semi-autonomous under the Dalai Lamas or regents. Qing authorities engaged in occasional military interventions in Tibet, intervened in Tibetan frontier defense, collected tribute, stationed troops, and influenced reincarnation selection through the Golden Urn. About half of the Tibetan lands were exempted from Lhasa's administrative rule and annexed into neighboring Chinese provinces, although most were only nominally subordinated to Beijing.[15]

By the late 19th century, Chinese hegemony over Tibet only existed in theory.[16] In 1890, the Qing and Britain signed the Anglo-Chinese Convention Relating to Sikkim and Tibet, which Tibet disregarded.[17] The British concluded in 1903 that Chinese suzerainty over Tibet was a "constitutional fiction",[18] and proceeded to invade Tibet in 1903–1904. However, in the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention, Britain and Russia recognized the Qing as suzerain of Tibet and pledged to abstain from Tibetan affairs, thus fixing the status of "Chinese suzerainty" in an international document,[19][20] although Qing China did not accept the term "suzerainty" and instead used the term "sovereignty" to describe its status in Tibet since 1905.[21] The Qing began taking steps to reassert control,[22] then sent an army to Tibet for establishing direct rule and occupied Lhasa in 1910.[23] However, the Qing dynasty was overthrown during the Xinhai revolution of 1911-1912, and after the Xinhai Lhasa turmoil the amban delivered a letter of surrender to the 13th Dalai Lama in the summer of 1912.[17] The 13th Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa in 1913 and ruled an independent Tibet until his death in 1933.[24]

- ^ Norbu 2001, p. 78: "Professor Luciano Petech, who wrote a definitive history of Sino—Tibetan relations in eighteenth century, terms Tibet's status during this time as a Chinese "protectorate". This may be a fairly value-neutral description of Tibet's status during the eighteenth century..."

- ^ Goldstein 1995, p. 3: "During that time the Qing Dynasty sent armies into Tibet on four occasions, reorganized the administration of Tibet and established a loose protectorate."

- ^ Dabringhaus 2014.

- ^ Di Cosmo, Nicola (2009), "The Qing and Inner Asia: 1636–1800", in Nicola Di Cosmo; Allen J. Frank; Peter B. Golden (eds.), The Cambridge History of Inner Asia: The Chinggisid Age, Cambridge University Press – via ResearchGate

- ^ Elliott 2001, p. 357.

- ^ Kapstein, Matthew (2013), The Tibetans, Wiley, ISBN 978-1118725375

- ^ Lamb 1989, pp. 2–3: "From the outset, it became apparent that a major problem lay in the nature of Tibet's international status. Was Tibet part of China? Neither the Tibetans nor the Chinese were willing to provide a satisfactory answer to this question."

- ^ Sperling 2004, p. ix: "The status of Tibet is at the core of the dispute, as it has been for all parties drawn into it over the past century. China maintains that Tibet is an inalienable part of China. Tibetans maintain that Tibet has historically been an independent country. In reality, the conflict over Tibet's status has been a conflict over history."

- ^ Sperling 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Hau, Caroline (2022), Siting Postcoloniality, Duke University Press, ISBN 9781478023951

- ^ Cheng, Hong (2023), The Theory and Practice of the East Asian Library, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 9781527592025

- ^ Szczepanski, Kallie (31 May 2018). "Was Tibet Always Part of China?". ThoughtCo.

- ^ Emblems of Empire: Selections from the Mactaggart Art Collection, by John E. Vollmer, Jacqueline Simcox, p154

- ^ Central Tibetan Administration 1994, p. 26: "The ambans were not viceroys or administrators, but were essentially ambassadors appointed to look after Manchu interests, and to protect the Dalai Lama on behalf of the emperor."

- ^ Klieger, P. Christiaan (2015). Greater Tibet: An Examination of Borders, Ethnic Boundaries, and Cultural Areas. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 71. ISBN 9781498506458.

- ^ Schoppa 2020, p. 324.

- ^ a b Tsering Shakya, "The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Tubten Gyatso" Treasury of Lives, accessed May 11, 2021.

- ^ International Commission of Jurists (1959), p. 80.

- ^ Ray, Jayanta (2007). Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World. Pearson Education. p. 197.

- ^ Klieger, P. Christiaan (2015). Greater Tibet: An Examination of Borders, Ethnic Boundaries, and Cultural Areas. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 74. ISBN 9781498506458.

- ^ Dolma, Tenzin (2020). Reviews on Tibetan Political History: A Compilation of Tibet Journal Articles. Library of Tibetan Works & Archives. p. 76.

- ^ India Quarterly (volume 7), by Indian Council of World Affairs, p120

- ^ Rai, C (2022). Darjeeling: The Unhealed Wound. Blue Rose Publishers. p. 55.

- ^ Schoppa 2020, p. 325.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search